di P. Paolo M. Siano

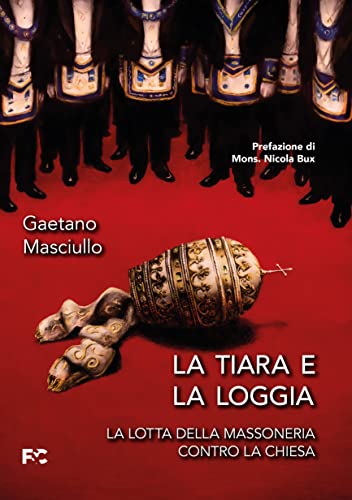

In questo saggio, Padre Siano recensisce il libro di Gaetano Masciullo, “La Tiara e la Loggia” (Fede & Cultura, Verona 2023).

Nel luglio 2023 l’Editrice Fede & Cultura di Verona ha pubblicato il libro di Gaetano Masciullo, “La Tiara e la Loggia. La lotta della Massoneria contro la Chiesa”, le cui tesi portanti (ed erronee) – che ho indicato e sottolineato nel titolo di questa recensione – contraddicono proprio quella letteratura antimassonica e antimondialista che l’Autore cita ed elogia.

Vediamo prima alcuni articoli con cui l’Autore ha lanciato il suo libro e poi entriamo nel testo de “La Tiara e la Loggia”.

- Alcuni articoli dell’Autore

Gaetano Masciullo, laureato in Filosofia all’Università di Bari e all’Università Italiana Svizzera (USI) di Lugano, giovane giornalista e scrittore, dall’ottobre 2021 Responsabile di Marketing e Comunicazione dell’Editrice Fede & Cultura[1], ha dato notizia del suo libro con l’articolo on-line “Dalla loggia alla società: il trionfo della mentalità massonica” pubblicato da “La Nuova Bussola Quotidiana” il 24 giugno 2023. Masciullo riconosce la difficoltà nell’analizzare il tema Massoneria:

«per via, da un lato, della rigida segretezza cui i massoni sono vincolati, una segretezza che rende ardua qualunque libera ricerca negli archivi delle logge da parte di coloro che delle logge non fanno parte; dall’altro lato, dalla sovrabbondanza di informazioni false e contraddittorie che circolano non solo sul web, ma anche spesso nella storiografia (sia di parte massonica sia di parte anti-massonica), informazioni che sono guidate più da scelte e pregiudizi ideologici, anziché dall’oggettiva verità dei fatti»[2].

Purtroppo, circa le «informazioni false e contraddittorie», almeno qualcuna si trova anche nel libro di Masciullo, come indicherò più avanti.

Secondo l’Autore il periodo che va dal 1717 al 1945 è:

«il periodo del “trionfo massonico” un periodo in cui le logge hanno davvero giocato un ruolo di notevole rilievo nel forgiare la mentalità filosofica, politica, economica e spirituale. Oggi dovremmo piuttosto parlare di “periodo post-massonico”. In effetti, la mentalità massonica – che trova in ultima istanza la propria radice nel pensiero gnostico – è ormai entrata così a fondo nel sentire comune che la Massoneria stessa quasi non ha più ragion d’essere: tutti oggi pensano con categorie gnostiche, non più cattoliche, senza avere più bisogno di essere iniziati nelle logge»[3].

Masciullo ritiene che la Massoneria speculativa, quella ufficialmente fondata nel 1717:

«non ha un’identità propria davvero propria: essa nacque dal bisogno di istituire un ricettacolo per tutte quelle tradizioni culturali e spirituali che avevano serpeggiato sotterranee nell’Europa cattolica medievale e in quella, già assai divisa, moderna. Cabalismo, catarismo, ermetismo, alchimia, rosacrocianesimo: tutte diverse declinazioni di uno stesso pensiero filosofico-teologico, antico tanto quanto lo stesso cristianesimo, e anzi con radici perfino più antiche: la gnosi, come si accennava»[4].

Il 26 giugno 2023 Masciullo pubblica un nuovo articolo, questa volta sul blog di Aldo Maria Valli, dal titolo: “Sul libro ‘La tiara e la loggia’/ In che senso siamo in un tempo post massonico”, dove rivela che «alcuni lettori sono rimasti perplessi» dinanzi alla sua datazione 1717-1945 quale periodo del “trionfo massonico”, e al definire il periodo attuale come “post-massonico”.

Masciullo dice che c’è un «fraintendimento», «una mala comprensione del prefisso “post” nell’espressione “post-massonico”», e aggiunge:

«Dire infatti che viviamo in un periodo post-massonico non significa dire che la Massoneria sia morta, che non sia più operativa, che non si interessi più di attività culturali, politiche o economiche. Semplicemente – come ho scritto nel testo – significa che la causa finale (ciò per cui una determinata cosa esiste, e quindi la ragion d’essere della cosa stessa) della Massoneria è stata conseguita»[5].

Masciullo si chiede «Quale è stata la causa finale della Massoneria?» (si noti il verbo “essere”, al tempo passato prossimo) e risponde indicando «almeno tre direttive»:

- Sostituire la cultura cattolica con una cultura gnostica

- Diffondere il socialismo a livello politico-economico

- Sottrarre alla Chiesa il potere temporale.

«Tutte queste tre direttive […] sono state raggiunte»[6].

Osservo che in realtà la Massoneria, dai primi Tre Gradi fino agli Alti Gradi, si propone chiaramente, nei suoi Statuti o Costituzioni, di realizzare la Fratellanza Universale, anzitutto tra gli Iniziati e poi tra gli Uomini tutti, dunque il Perfezionamento Iniziatico e Universale, ragion per cui, strettamente parlando, quella che Masciullo chiama «causa finale» della Massoneria non è pienamente realizzata…

Proseguiamo con l’articolo di Masciullo, il quale afferma:

«Certo la Massoneria esiste, ed è ancora operativa (in gradi differenti), sia per conservare la Rivoluzione sia per portare a termine questi effetti. Ma la causa finale della Massoneria è stata conseguita, e la Massoneria è di fatto “inutile”, nel senso che sono tantissime le istituzioni che lavorano per sviluppare gnosi e socialismo senza essere iniziate nelle logge. Ci sono altri che possono benissimo lavorare al posto dei massoni, e che sono altrettanto organizzati, se non addirittura maggiormente organizzati. Quando un ente diventa inutile perché ha raggiunto il proprio obiettivo, non è automatica la sua morte, la sua sparizione. Siamo pieni di istituzioni inutili, obsolete, eppure ancora vive. I bersaglieri e le guardie svizzere sono due esempi eclatanti»[7].

In realtà, contrariamente a quanto afferma Masciullo, i Bersaglieri (https://www.esercito.difesa.it/concorsi-e-arruolamenti/pagine/bersagliere.aspx) e le Guardie Svizzere (https://www.guardiasvizzera.ch/paepstliche-schweizergarde/it/chi-siamo/) non sono affatto «istituzioni inutili, obsolete».

Poi Masciullo scrive:

«Oggi tutte le istituzioni (scuola, università, cinema, media, ecc.) pensano come massonerie senza grembiule. Questo però non vuol dire che la Rivoluzione sia finita. L’errore che si fa molto spesso, e che potrebbe avere causato il fraintendimento che voglio qui chiarire, è quello di confondere e di far coincidere la Rivoluzione con la Massoneria, dimenticando che la Massoneria è solo uno strumento, certo il più efficace, della Rivoluzione. Come scrivo nel libro, la spada della Rivoluzione è ormai affidata ad altre entità esterne alla Massoneria, in primis alla componente modernista della Chiesa cattolica. Quando si comprende che la Rivoluzione è un fenomeno ben più grande della Massoneria, allora si capisce perché parlo di periodo massonico e periodo post-massonico»[8].

Masciullo non dice chi mantiene la spada della Rivoluzione, ossia quale entità (visibile o invisibile?) dirige la Rivoluzione escludendone addirittura la Massoneria… Masciullo vuol farci credere che la Massoneria si sia ritirata lasciando posto al clero modernista… In realtà Massoneria & Modernismo coesistono e sono alleati…

Ancora Masciullo:

«I massoni del Sette e Ottocento bene avevano compreso che, per distruggere l’ordine cattolico, bisognava instillare nelle menti dell’èlite politica una visione nuova del cosmo. Il fatto che massoni abbiano lavorato per rendere vittoriose la rivoluzione sovietica, la rivoluzione del sessantotto e la rivoluzione del gender non comporta che quanto detto finora sia sbagliato»[9].

Si tenga a mente questa frase di Masciullo che ho sopra citato: «il fatto che massoni abbiano lavorato per rendere vittoriose la rivoluzione sovietica, la rivoluzione del sessantotto e la rivoluzione del gender»… Come vedremo più avanti, nel libro in questione, Masciullo sembra far capire che Massoneria o Massoni non avrebbero a che fare con ’68 e Gender…

- Alcune tesi dal libro dell’Autore.

Vediamo alcuni punti del libro “La Tiara e la Loggia”.

- La Massoneria è la Contro-Chiesa, ma in declino…

Masciullo scrive:

«La Massoneria è una contro-Chiesa, anzi la contro-Chiesa per eccellenza. Bisogna però ammettere allo stesso tempo che la Massoneria oggi ha terminato la sua funzione storica. Le logge non sono più fiorenti come un tempo, come avveniva tra Sette e Ottocento – il “secolo del trionfo massonico” – o ancora nella prima metà del Novecento»[10].

Non è vero che le Logge non sono più fiorenti, e non è vero che la Massoneria è in declino. Se – come ammette Masciullo e la letteratura antimassonica da lui citata – la Massoneria è «la contro-Chiesa per eccellenza»[11], allora la Massoneria non ha esaurito affatto la sua funzione, poiché la Chiesa esiste ed esisterà. Insomma, Masciullo si contraddice.

Masciullo prosegue:

«Un ente perde la propria funzione quando è sconfitto da un ente con una funzione opposta, oppure quando raggiunge il proprio fine. Nel nostro caso, possiamo affermare con lucidità e certezza che la Massoneria ha ben raggiunto il proprio scopo: a livello filosofico, la diffusione del pensiero gnostico (anche se in diverse varianti “volgarizzate”) e, a livello politico, la diffusione del socialismo a tutti i livelli e in tutte le nazioni del mondo»[12].

Masciullo prosegue nella sua descrizione irreale, depistante, falsa, della Massoneria, presentandola come realtà ormai insignificante e in declino:

«Non dobbiamo infatti pensare che la Massoneria sia l’unica faccia del nemico. La Massoneria è stata solo un mezzo per condurre una guerra che è ben più vecchia di quella iniziata nel 1717, l’anno ufficiale di nascita della prima loggia massonica, e che procede ancora oggi, anche se le logge sono oramai ridotte a ritrovi di anziani ricchi e filantropi. La Massoneria è stata certamente fino a oggi il mezzo più organizzato della guerra contro la Chiesa cattolica, e quindi il più efficace. Oggi la spada della lotta è stata affidata ad altre entità – per esempio, agli stessi uomini di Chiesa che propugnano la teologia modernista – […]»[13].

Masciullo fa capire che ci sia stato un passaggio di consegne tra Massoneria e chierici modernisti… Ma non è così. La Massoneria non è in declino e non si ritira.

- La Massoneria, erede della Gnosi o Gnosticismo.

Masciullo scrive:

«All’origine di questa dottrina [nota mia: circa il perfezionamento massonico in termini e simboli muratori] c’è una religione molto antica, chiamata gnosi o gnosticismo, di cui la Massoneria si presentava (e si presente tuttora) come l’unica vera erede»[14].

Sì, la Massoneria comprende in sé la Gnosi. Su questo mi trovo d’accordo con l’Autore.

- Albert Pike e i gradi del RSAA

Circa l’opera fondamentale del massone Albert Pike 33°, “Morals and Dogma” (1871), Masciullo scrive:

«Morals & Dogma è un testo molto importante per comprendere meglio il significato e la rivelazione iniziatica dei 33 Gradi della Massoneria moderna»[15].

In realtà, Pike commenta fino al 32° grado incluso. Non dice nulla sul 33° grado.

Masciullo vuole offrire una sintesi dei 33 gradi del RSAA[16] secondo quanto spiegato dal massone Albert Pike :

«La spiegazione di ciascun Grado è una sintesi di quanto esposto da Albert Pike all’interno del suo libro. Per approfondire, cfr. Albert PIKE, Morals & Dogma of Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, Kessinger Publishing, 2010»[17].

In realtà, nelle pagine successive (pp. 198-208) in cui spiega i 33 gradi, non mi pare di vedere una sintesi tratta da “Morals and Dogma” di Albert Pike, quanto piuttosto una sintesi tratta da qualche testo antimassonico in cui si parla, ad esempio, dei 33 gradi suddivisi in tre serie di 11 (come, ad esempio, sulla rivista “Chiesa Viva” N. 420 – Ottobre 2009, pp. 23-24.27, oppure nel libro “La Franc-Maçonnerie Synagogue de Satan” di Mons. Leone Meurin, 1895), suddivisione che non ho mai riscontrato finora in testi massonici.

Masciullo (appunto come quei testi antimassonici che dividono i 33 gradi RSAA in tre gruppi da “11”) sostiene che la Massoneria “rossa” comincia dal 12° grado[18]. In realtà, nel RSAA la cosiddetta Massoneria Rossa comincia dal 4° grado e giunge fino al 18°.

In quella spiegazione apparentemente attinta da Pike, Masciullo parla anche del 33° grado[19], ma ribadisco che purtroppo Pike, in Morals & Dogma, non parla affatto del 33° grado.

- Donne in Massoneria, «rare eccezioni?»

Masciullo scrive in una nota:

«A parte rare eccezioni, la Massoneria ha sempre accolto tra gli iniziati esclusivamente persone di sesso maschile»[20].

Mi permetto di correggere anche in questo l’Autore: quelle «rare eccezioni» avvenivano, semmai, nel secolo XVIII, ma poi a partire dalla seconda metà del secolo XIX e specialmente dalla prima metà del secolo XX fino al presente, sono sorte varie Grandi Logge miste (maschili e femminili) e addirittura Grandi Logge Femminili, che sono a tutti gli effetti “Massoneria”. Attualmente molte, se non tutte, Grandi Logge sia “miste” che esclusivamente femminili, fanno parte dell’imponente Circuito Massonico legato in qualche modo al Grand Orient de France.

- La teoria del “Palladismo” o quella della “Massoneria di frangia”?

Masciullo dà grande importanza alla letteratura antimassonica, specialmente di area tradizionalista, italiana e francese, che crede nell’esistenza del Palladismo, ossia il presunto vertice direzionale della Massoneria mondiale dedito al culto di Lucifero, inteso come Dio di Luce, contro il Dio di noi Cristiani inteso come Dio delle Tenebre… Nel Palladismo, «super-loggia massonica», verrebbero cooptati solo massoni dal 30° grado (RSAA o Rito di Memphis-Misraim) in su[21]. In effetti, Masciullo rimanda in nota alle pagine 111-113 del libro di Epiphanius, “Massoneria e le sette segrete”[22].

Questa tesi, Alta Massoneria=Palladismo=Luciferismo, è rigettata sia dalle dichiarazioni ufficiali o ufficiose di Massoni, e sia da studiosi cattolici come Massimo Introvigne, il quale appunto restringe l’interesse massonico verso la Magia & Lucifero/Satana a quelle che lui definisce “Massonerie di frangia” ovvero “marginali”… I lettori dei miei libri e saggi pubblicati qui su Fides Catholica e sul sito www.corrispondenzaromana.it, sanno bene che su questo punto divergo da Introvigne: in realtà, Magia & Lucifero interessano anche Massoni e Massonerie regolari! Ovviamente non possiamo pretendere che ce lo confessino apertamente in dichiarazioni ufficiali. La Massoneria è una Setta Iniziatica, Esoterica, Gnostica, che nasconde molte cose a noi Profani…

Ora, Masciullo sembra condividere la tesi di Introvigne allorché parla de:

«l’esistenza di frange esoteriche e perfino massoniche (queste ultime in realtà davvero marginali e perfino malviste dalle obbedienze libero-muratorie principali) che avevano fatto del liturgismo satanico il cardine della propria attività202»[23].

Nella nota 202, a pié pagina 223, Masciullo cita la teoria «di “massoneria di frangia”» e Massimo Introvigne…

Se si accoglie la teoria secondo cui esiste il Palladismo, o quantomeno un culto luciferiano tra Massoni di Alti Gradi (es.: RSAA), che non sono affatto Massoni “marginali”, logicamente non si può accogliere in tutto anche la teoria negazionista o minimista della cosiddetta “Massoneria frangia”, teoria, questa, diffusa in Italia, tra i Cattolici, da Massimo Introvigne (almeno dal 1993 in poi), ma “inventata” dal massone inglese Ellic Howe verso la metà degli anni ’70 del secolo XX.

Mi sembra che Masciullo metta insieme autori e dati (Epiphanius & Introvigne, teorie Palladismo & Massoneria di frangia…) senza evidenziarne la reciproca contraddizione.

- Massoneria in declino?…

“Il Mondialismo e la variante cinese del ‘socialismo esoterico’ ” (pp. 271-280) è l’ultimo capitolo del libro “La Tiara e la Loggia”. Masciullo ritiene che:

«nel 1945 è terminata l’epoca massonica della storia moderna»[24]; «la Massoneria oggi ha terminato la propria funzione storica e ciò perché un qualunque ente perde la propria funzione quando è sconfitto da un ente con una funzione opposta, oppure quando raggiunge il proprio fine»[25].

Masciullo è convinto che «la Massoneria ha ben raggiunto il proprio scopo: a livello filosofico, la diffusione del pensiero gnostico (anche se in diverse varianti “volgarizzate”) e, a livello politico, la diffusione del socialismo a tutti i livelli e in tutte le nazioni del mondo»[26].

In realtà questa teoria o ricostruzione di Masciullo non è storia, ma è ideologia. Non corrisponde alla realtà dei fatti. La Massoneria non è in declino.

Masciullo afferma che il suo libro, poiché non è un saggio sulla storia della Rivoluzione ma sulla storia e sul pensiero della Massoneria, non si occupa perciò dei fatti rivoluzionari successivi al 1945, come il Sessantotto e la gender theory[27]… È strano che Masciullo arresti l’influenza della Massoneria al 1945… Egli, sì, riconosce che la Massoneria è «formalmente viva come istituzione» ma ritiene che essa «non è più attiva e decisiva così come lo è stata nei secoli passati per quanto riguarda le lotte sociali e culturali»[28].

Mi sembra che queste affermazioni di Masciullo siano contraddette proprio da lui stesso che, nel suo articolo on-line del 26 giugno 2023 (come ho riportato nel paragrafo 1), sembra invece attribuire ai Massoni anche il Sessantotto e la teoria del gender[29]. Invece qui, nel libro, egli separa o esclude la Massoneria dal Sessantotto e dalla gender theory[30]… Con disinvoltura, senza preavviso, l’Autore passa da una tesi all’altra e il lettore attento resta disorientato notandone la contraddizione.

Masciullo prosegue giustificando così la sua teoria circa il presunto declino della Massoneria:

«Il pensiero massonico ha talmente permeato la società contemporanea che gli individui pensano e agiscono con categorie gnostiche e massoniche senza neanche rendersene conto, senza dunque che vi sia la necessità di essere iniziati e formati nelle logge»[31].

In realtà, la diffusione del pensiero massonico oltre la Massoneria, non vuol dire necessariamente che essa sia in declino o che abbia esaurito la sua funzione. Anzi…

Masciullo prosegue accennando ad ambienti iniziatici o mondialisti americani, poi parla della Cina, delle “Triadi” cinesi, dell’azione del governo cinese nel mondo e infine, accenna al modernismo nella Chiesa[32]… Così termina il libro “La Tiara e la Loggia”.

In effetti Masciullo si rifà anche al libro di Gianni Vannoni (che egli cita), “Le società segrete dal Seicento al Novecento. Note e documenti” (Sansoni Editore, Firenze 1985), il cui penultimo e ultimo capitolo si intitolano rispettivamente: “Ombre cinesi” (pp. 319-321) e “Il motore segreto della politica statunitense” (pp. 323-325). Ma Vannoni non dice affatto che la Massoneria sia in declino dal 1945.

Torno a ribadire che in realtà, dal 1945, la Massoneria non è affatto in declino. Al riguardo, mi permetto di segnalare alcuni miei saggi on-line:

- Una fonte citata da Masciullo: Epiphanius, “Massoneria e sette segrete…”

Un autore che Masciullo ritiene molto importante nello studio della Massoneria e dei gruppi o società segrete del Mondialismo o Governo Occulto mondiale, è Epiphanius, “Massoneria e sette segrete: la faccia occulta della storia”, Nuova edizione rivista e corretta, Editrice “Ichthys”, Albano Laziale (Roma) 2004, 776 pagine. Alle pp. 5-6, c’è la lettera-prefazione di Henri Coston (1910-2001) all’edizione francese. Coston è uno dei maggiori studiosi del XX secolo sul fenomeno del Mondialismo.

Epiphanius si appoggia a studiosi cattolici critici verso il Mondialismo, quali Henri Coston, Pierre Faillant de Villemarest, Pierre Virion, Yann Moncomble…

Il libro è pubblicato da un’editrice legata alla Fraternità Sacerdotale San Pio X (FSSPX). Dal testo di Epiphanius traspare un giudizio assai negativo verso il Concilio Vaticano II. Al lettore può venire il sospetto che uno degli scopi primari del testo di Epiphanius, al di là dell’informazione antimondialista e antimassonica, sia demonizzare l’intero Concilio e l’intera Chiesa Post-Conciliare presentandola in toto come alleata di Massoneria & Mondialismo… Esorterei i tradizionalisti ad avere molta cautela per non fare di tutta un’erba un fascio. La Massoneria sa giocare non solo a sinistra, ma anche a destra…

3.1. Massoneria=Controchiesa.

Epiphanius parla della «Controchiesa» in cui si manifestano l’«Alta Loggia» e l’«Alta Finanza»[33] e che vuole realizzare il «Governo Mondiale»[34]. Epiphanius definisce il Concilio Vaticano II: «drammatico e infausto evento»[35].

Un altro studioso cattolico del mondialismo è Pierre Virion (1898-1988), già collaboratore di Mons. Ernest Jouin (1844-1932) che fu il fondatore della “Revue Internationale des Sociétés Secrètes’’ fondata a Parigi nel 1912[36].

Virion – ed Epiphanius – ritiene che esista un «potere direzionale» nella Massoneria[37].

3.2. Come verificare la letteratura antimondialista?

Epiphanius riporta tantissime citazioni, dirette o indirette, di massoni o uomini di grande potere che annunciano o auspicano un Governo Mondiale. Le citazioni riportate sono tutte vere? Il lettore medio si accontenta e prende tutto per vero e per certo. Lo studioso invece, vorrebbe risalire alle fonti e verificare citazione per citazione. Purtroppo non è sempre possibile. Personalmente, non posso fondare i miei studi sugli studi di antimassoni e antimondialisti. Quando devo scrivere qualcosa su questi argomenti, cerco fonti dirette, cioè fonti provenienti da ambienti massonici. Non mi occupo molto di Mondialismo dato che non è sempre facile giungere a fonti sicure (riviste, documenti di certi gruppi o personaggi di potere…). Invece, in un certo senso, è più facile reperire fonti massoniche.

3.3. Gli Illuminati di Baviera, davvero così importanti?

Il libro di Epiphanius tratta temi interessanti: la Gnosi, la Cabala, i Rosacroce, la Massoneria, il Martinismo, gli Illuminati Baviera[38]. Circa questi ultimi, mi chiedo se Epiphanius ed altri diano agli Illuminati di Baviera più importanza di quella che ebbero. Infatti i Massoni regolari, specialmente quelli del 33° grado Scottish Rite, si autodefiniscono «Illuminati»[39], perciò ritengo che i “33” siano ben più importanti degli “Illuminati di Baviera” che invece sono stati fondati e soppressi nella seconda metà del XVIII secolo.

Epiphanius sostiene che l’Ordine “Skull & Bones” (a cui apparteneva anche il Presidente USA George Bush Senior) sia una derivazione o prosecuzione degli Illuminati di Baviera[40]… Chi parla degli Illuminati di Baviera è anche l’ammiraglio William Guy Carr nel suo libro “Pawn in the Game” citato da Epiphanius[41].

3.4. Una rivista che non c’è…

A pag. 124, Epiphanius scrive che:

«nell’ottobre 1924 a p. 69 della rivista L’Acacia massonica del Grande Oriente d’Italia apparve un’Arringa per Satana […]»[42].

Poi Epiphanius cita brani di quell’articolo, in italiano, inneggianti a Satana-Lucifero. Però alla nota 251, a pié pagina 124, invece di citare il suddetto articolo massonico, Epiphanius cita una rivista francese: «Lecture Française, n. 466, febbraio 1996, p. 7».

Evidentemente Epiphanius cita l’articolo massonico citato da una rivista francese antimassonica o antimondialista, forse anche cattolico-tradizionalista… Ecco il problema dell’antimassoneria tradizionalista; indulgere troppo in citazioni indirette, cioè citazioni di fonti antimassoniche…

Ho cercato quell’articolo e ho scoperto che:

- nel 1924 nessuna rivista massonica del GOI si intitolava “L’Acacia massonica”. Il Rito Simbolico Italiano, del GOI, aveva una rivista, “L’Acacia”, cominciata nel 1908 ma finita nel 1917.

- in realtà si tratta della rivista del Grand Orient de France, “L’Acacia”, ottobre 1924, l’articolo è “Plaidoyer pour Satan”. Dunque la rivista e l’articolo sono in lingua francese, della Massoneria francese!

Insomma, l’errore di Epiphanius è da matita blu. Perciò preferisco non appoggiarmi al suo libro (come fanno invece certi antimassoni o antimondialisti dei nostri giorni), a meno che io non riesca poi a verificare le sue affermazioni e citazioni, ricorrendo alle stesse fonti citate o eventualmente ad altre migliori.

3.5. Il Palladismo e la corrispondenza Pike-Mazzini…

Il capitolo VIII, “Il Palladismo ovvero la necessità di un vertice” (pp. 119-127), tratta del Luciferismo massonico riservato ai massoni del 30° grado RSAA e a quelli dei gradi equivalenti del Rito di Memphis-Misraim[43]. Il Palladismo aveva 3 gradi (Kadosh palladico, Gerarca palladico, Mago eletto) e si collocava (Epiphanius scrive «collocava») al di sopra dei Supremi Consigli del 33° grado RSAA… All’origine del “New and Reformed Palladian Rite” c’erano Albert Pike e Giuseppe Mazzini[44]. Quando Pike morì nel 1891, il Palladismo supervisionava le Massonerie americane e lo Scozzesismo massonico mondiale, ispirando e appoggiando il movimento rivoluzionario[45].

Il caso del Palladismo è molto controverso, poiché è intrecciato al caso Leo Taxil, su cui ho scritto qualcosa[46].

Epiphanius accenna alla corrispondenza tra Mazzini e Pike 1870-1871… La lettera di Mazzini a Pike del 22 gennaio 1870… La lettera di Pike a Mazzini del 15 agosto 1871[47]. Epiphanius scrive che secondo Jean Lombard questa corrispondenza Mazzini-Pike è conservata negli archivi del “Temple House”, sede dello Scottish Rite di Washington, e ne è vietata la consultazione… Ma la lettera di Pike a Mazzini del 15 agosto 1871 sarebbe stata una volta esposta al British Museum Library di Londra e visionata da un ufficiale della Marina canadese, William G. Carr (che nel 1945 partecipò alla Conferenza di San Francisco come consulente degli USA). Carr vide quella lettera e ne fece un riassunto nel suo libro “Pawns in the Game”[48]. Dal 1927 al 1930 Carr fece parte del gruppo dell’ammiraglio Barry Domville, direttore del British Naval Intelligence[49].

Epiphanius ha fiducia nel libro e nelle dichiarazioni dell’ammiraglio William Guy Carr circa la corrispondenza Mazzini-Pike, in cui già si parla di 3 guerre mondiali… La terza sarà tra sionismo e mondo musulmano[50]… Nella presunta lettera del 15 agosto 1871 Pike direbbe che dopo la terza guerra mondiale scoppierà un grande cataclisma sociale, ci sarà la manifestazione della pura dottrina di Lucifero e l’annientamento della Cristianità e dell’ateismo[51]…

Poi Epiphanius parla del Risorgimento italiano, le società segrete europee, il Socialismo, la Sinarchia, la Rivoluzione bolscevica, la Società delle Nazioni, la Teocrazia Luciferiana, il Movimento Paneuropeo, la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, l’ONU, il Governo Mondiale, l’UNESCO, le Campagne dell’ONU (ecologismo e animalismo), Pornografia-Droga-Mondialismo, gli Stati Uniti d’Europa, l’Età dell’Acquario, il Lucis Trust (tra i cui sostenitori aveva anche Henry C. Clausen 33°, l’allora Sovrano Gran Commendatore del RSAA di Washington[52]). E poi, il New Age e i suoi tre obiettivi: governo mondiale, religione mondiale, istruzione pubblica planetaria[53].

Epiphanius conosce il caso di Leo Taxil e della presunta circolare luciferiana di Albert Pike, che poi verrà smentita da Taxil come una sua invenzione… È degno di nota che Epiphanius (e l’avevo scoperto anch’io prima di leggere il suo libro) trova somiglianze tra brani di “Morals and Dogma” di Albert Pike e quella presunta circolare luciferiana di Pike. Inoltre Epiphanius cita un brano in cui il massone Manly Palmer Hall 33° loda Lucifero (e anche quel brano l’ho scoperto prima di leggere Epiphanius)[54].

Nel suo libro, circa il Luciferismo massonico, Epiphanius cita Leo Taxil, ma non cita Domenico Margiotta, che invece è un autore più importante, come ho già indicato, in parte, in un mio studio su “Fides Catholica”.

3.6. La tesi di Epiphanius contro quella di “La Tiara e la Loggia” ?

Secondo Epiphanius, Lucifero è il vertice della piramidale «Controchiesa Sinarchica». Sotto Lucifero (il vertice), al primo livello superiore della piramide c’è l’ «Autorità», ossia «Maghi ispiratori» e «Teocrazia». A questo livello si inserisce il Lucis Trust. Scendendo la piramide, segue, al secondo livello, il B’nai B’rith e le varie Massonerie di Alti Gradi. Poi, scendendo, al terzo livello, l’Alta Finanza, ONU, Fabian Society, Order… Al quarto livello: varie associazioni massoniche (i gradi bassi) e associazioni paramassoniche tra cui Rotary e Lions… Al 5° livello: socialismo tecnocratico, repubbliche popolari, uomini politici, popolo[55].

Dunque nella «Controchiesa Sinarchica», al secondo livello superiore della piramide, dopo il B’nai B’rith, ci sono le Massonerie degli Alti Gradi ovvero: Martinisti, Rosacrociani (S.R.I.A., O.T.O.), Teosofia, Side Masonry, Supremi Consigli dei 33, e anche Bilderberg, Round Table[56]…

Poi, nel libro, seguono tre Appendici: I finanziatori della Rivoluzione russa; le principali associazioni mondialiste (B’nai B’rith, Round Table, Royal Institute of International Affairs, Council of Foreign Relations, Trilateral Commission… ; la dichiarazione universale dei diritti dell’animale (UNESCO).

Non posso provare che tutto quanto scriva Epiphanius sia vero (ad esempio, tutti i livelli della Piramide). Quantomeno è interessante notare che secondo Epiphanius, le Massonerie degli Alti Gradi occupano un posto elevato nella Controchiesa, ossia nella gerarchia anticattolica e mondialista.

Quello di Epiphanius è un libro ampio, interessante, forse con troppi argomenti. Ci sono certamente notizie vere, ma forse sono troppe le citazioni da fonti indirette, ossia da studiosi antimassoni o antimondialisti, le cui notizie non sono tutte accurate (vedi sopra: il caso dell’articolo de L’Acacia 1924), né verificabili (il caso Mazzini-Pike e “Pawns in the Game”).

In ogni caso, mi sembra che il poderoso volume di Epiphanius non presti il fianco alla tesi portante del libro di Masciullo secondo il quale dal 1945 si entrerebbe nel periodo post-massonico in quanto la Massoneria sarebbe diventata ormai ‘inutile’ al Piano della Rivoluzione, pertanto la Massoneria sarebbe in declino… Invece secondo Epiphanius, la Massoneria è quasi al vertice della Contro-Chiesa, ancora attuale.

Insomma, Masciullo attinge a piene mani da tale letteratura antimassonica e antimondialista, ma la supera, la contraddice e la sintetizza (hegelianamente?) con la sua teoria del periodo post-massonico e della inutilità o declino della Massoneria.

Concludo osservando che di fatto il libro di Masciullo, per quanto sia pubblicizzato come antimassonico, di fatto reca un bel servizio alla Massoneria poiché distoglie da essa l’attenzione dal 1945 in poi…

Nel 2022, circa un anno prima della pubblicazione del libro “La Tiara e la Loggia”, un massone, sedicente convertito (di cui non posso rivelare l’identità), mi ha detto che la Massoneria non ha nulla a che fare con magia e luciferismo, inoltre mi ha ripetuto la teoria della “Massoneria di frangia”, e mi ha detto anche che oggi la Massoneria non conta più, non è più importante come in passato[57], e quest’ultima è, in sostanza, la tesi del libro di Masciullo. Ma non mi ha convinto.

______________________________

[1] https://it.linkedin.com/in/gaetano-masciullo-601192148

[2] https://lanuovabq.it/it/dalla-loggia-alla-societa-il-trionfo-della-mentalita-massonica, grassetto mio.

[3] Ibidem, grassetto mio.

[4] Ibidem.

[5] https://www.aldomariavalli.it/2023/06/26/sul-libro-la-tiara-e-la-loggia-in-che-senso-siamo-in-un-tempo-post-massonico/

[6] Ibidem.

[7] Ibidem, grassetto mio.

[8] Ibidem, grassetto mio.

[9] Ibidem, grassetto mio.

[10] Gaetano Masciullo, La Tiara e la Loggia. La lotta della Massoneria contro la Chiesa, Prefazione di Mons. Nicola Bux, Fede & Cultura, Verona 2023, p. 15, corsivo del testo, grassetto mio.

[11] Ivi, p. 15, corsivo del testo.

[12] Ivi, pp. 15-16.

[13] Ivi, p. 16, corsivo del testo, grassetto mio.

[14] Ivi, p. 20, corsivo del testo.

[15] Ivi, p. 198.

[16] Cf. ivi, pp. 198-208.

[17] Ivi, p. 198, nota 181.

[18] Cf. ivi, p. 202.

[19] Cf. ivi, p. 208.

[20] Ivi, p. 198, nota 182.

[21] Cf. ivi, pp. 197-198.

[22] Cf. ivi, p. 198, nota 180.

[23] Ivi, p. 223, grassetto mio.

[24] Ivi, p. 272.

[25] Ivi, p. 272, grassetto mio.

[26] Ivi, p. 272.

[27] Cf. ivi, p. 272.

[28] Ivi, p. 272, grassetto mio.

[29] Cf. https://www.aldomariavalli.it/2023/06/26/sul-libro-la-tiara-e-la-loggia-in-che-senso-siamo-in-un-tempo-post-massonico/

[30] Cf. A. Masciullo, La Tiara e la Loggia, op. cit., p. 272.

[31] Ivi, pp. 272-273.

[32] Cf. ivi, pp. 273-280.

[33] Cf. Epiphanius, “Massoneria e sette segrete: la faccia occulta della storia”, Nuova edizione rivista e corretta, Editrice “Ichthys”, Albano Laziale (Roma) 2004, p. 10.

[34] Ivi, p. 11.

[35] Ivi, p. 11.

[36] Cf. ivi, p. 15.

[37] Cf. ivi, p. 15.

[38] Cf. ivi, pp. 87-117.

[39] Albert Gallatin Mackey 33°, An Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry and its kindred sciences comprising the whole range of arts, sciences and literature as connected with the institution, New and Revised Edition prepared under the direction and with the assistance of the late William J. Hughan 32° [Past Grand Deacon (England), Past Grand Warden (Egypt), Past Grand Warden (Iowa), Past Assistant Grand Sojourner (England), one of the founders Quatuor Coronati Lodge (London)], by Edward L. Hawkins 30° [Prov. S.G.W. (Sussex), P. Prov.S.G.W. (Oxfordshire), member Quatuor Coronati Lodge (London)], 2 volumes [Volume I: A-L, pp. VII, 1-455. Volume II: M-Z, pp. 457-913], The Masonic History Company, Chicago – New York – London 1921., Vol. I, art. Illuminati, p. 346.

[40] Cf. Epiphanius, “Massoneria e sette segrete, op. cit., pp. 107-113.

[41] Cf. ivi, p. 114.

[42] Ivi, p. 124.

[43] Cf. ivi, p. 119.

[44] Cf. ivi, p. 119.

[45] Cf. ivi, p. 121.

[46] https://www.corrispondenzaromana.it/un-ricordo-su-mons-ingo-dollinger-1929-2017/

[47] Cf. Epiphanius, “Massoneria e sette segrete, op. cit., pp. 125-126.

[48] Cf. ivi, p. 126, testo e nota 255.

[49] Cf. ivi, p. 126, nota 255.

[50] Cf. ivi, p. 126.

[51] Cf. ivi, p. 127.

[52] Cf. ivi, pp. 494-495.

[53] Cf. ivi, p. 553.

[54] Cf. ivi, pp. 584-585.

[55] Cf. ivi, p. 618.

[56] Cf. ivi, p. 618.

[57] https://www.corrispondenzaromana.it/tracce-di-esoterismo-in-side-degrees-o-appendant-orders-della-ugle-1a-parte/